What, How & for Whom / WHW: Art Always Has Its Consequences

One of the most famous episodes of guerrilla art protest actions carried out in a museum institution is a series of actions by the group GAAG (Guerilla Art Action Group) in the period from 1969 to 1971, especially because their protests were carried out in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a museum which even today, after its transformation from an elitist temple of aesthetic contemplation into a tourist attraction, maintains its position as the main institution of contemporary global art. Combining street theatre, happenings, political protests and collectivism, the actions of GAAG (1) fit in with other art collectives of the time, especially with the Art Workers Coalition (2). Their actions were directed against the war in Vietnam, against the involvement of members of the Museum of Modern Art’s management in corporations which profited from the Vietnam War (for example, they demanded the Rockefeller family’s withdrawal because their philanthropic involvement serves to cover up the fact that a great part of their wealth was created by the production and sale of arms), and stood for civil rights, the sexual and racial equality of artists, free museum days in order to bring art closer to the poor, etc. These actions bear witness to the unselfish belief that artists who care about social matters should join together and act outside the fetishized boundaries of museums and galleries. Photographs of those actions were published in the book GAAG, the Guerrilla Art Action Group, 1969–1976: A Selection (Printed Matter, New York, 1978) which can no longer be obtained today and which still has not found anybody in American museum and gallery culture to republish it. The aesthetics of those photographs is close to documentary and reportage photography which in those years recorded massive (pop)cultural events and political protests by young people in America.

The anti-war protests of those years fuelled the political imagination of a generation on both sides of the Iron Curtain, as an example in Miklós Erdély’s work The Algebra of Morals – Actions of Solidarity from 1972, which in the repressive atmosphere of Hungary’s then official art protested against the threat of war and called for solidarity which “surpasses leaders and the led, conflicting countries or groups, guards and guarded – solidarity which, for example, shows that the similarity between prisoner and jailer is greater than that between jailor and jail or between prisoner and imprisonment”.

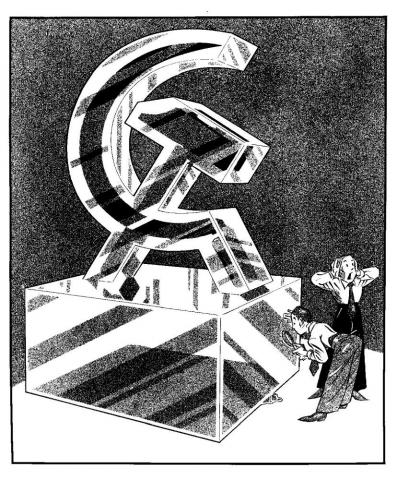

At that time the first signs of the transformation of the political and economic structure of the world that was established after the Second World War were just beginning to come into sight. One of the symptoms of that transformation is the recent crash of the financial markets and the economic crisis whose direct effects appear to have been softened by unprecedented state interventions, but whose lessons it seems have not been taken seriously. At a time, the so-called international art scene which came into being by the broadening of neo-liberal politics after 1989 did not exist, and nothing has had particularly endangered the dynamics of centre and periphery. Those were the years when the idea of modernist abstraction as a universal language of art entered into crisis, especially in the West, but also in countries behind the Iron Curtain where abstraction as a form which is equated with the idea of freedom of art and autonomy frequently also bore the stamp of art which resists the official ideological instrumentalisation of art, and which in the 1950s really inspired the international movements which connected the language of modernistic abstraction with the ideas of universal human emancipation.

This thought was in the background of “Didactic Exhibition on Abstract Art”, which was organised from 27 March to 30 April 1957 in the then still very new City Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb (officially founded in December 1954) by artists and critics who had until recently been gathered around the group EXAT 51 (which had then already ceased to work) and the magazine Čovjek i Prostor (3), and which travelled around former Yugoslavia (4) until 1962 bringing abstract art closer to the general public. That exhibition which is largely forgotten today shows the degree to which abstract art had really ceased to be problematic in the former Yugoslavia as early as the second half of the 1950s, but in the contemporary, so-called transitional, post-socialist period, that fact is interpreted in accordance with a particular ideological vision of the cultural history of Yugoslavia. On the one hand it is understood as a cliché about the strong domestic social realism and the struggle for modern art in opposition to the official party line, which frequently also leads to the thesis about the struggle for modern art as a kind of form of resistance of the remains of the threatened bourgeois society, the aspiration to “join the main current of European culture” to which we have, of course, always belonged, and on the other hand the extended arm of the all-powerful Party is seen in the very breakthrough of abstraction, a Machiavellian manipulation by which the totalitarian system presented itself to the world with a nice facade.

Contemporary misunderstandings about the understanding of modernism and its international option are part of the prevailing wide neo-liberal relationship towards socialism as a failed social experiment which resulted in economic, political and social catastrophe which needs to be overcome by “transition” whose price is not to be questioned. In relationship to art the consequence is, amongst other things, a history of art which oscillates between demonstrating its autochthony and establishing precedence or synchronicity with Western art centres. Examining the dominant art history narratives and relationships towards the socialist inheritance forms basis for the works of younger artists, such as David Maljković who in a range of works is concerned with the heritage of the group EXAT 51, or Andreas Fogarasi whose work Vasarely Go Home (Announcement) from 2010 interprets the action of neo-avant-garde artist János Major at the pompous official opening of a solo exhibition of the leader of non-figurative art, Victor Vasarely, a Hungarian who lived and worked in France, in Budapest in 1969. The documentary presentation of Art Symposium Wroclaw ’70, which holds a mythical place in the establishment of the beginnings of conceptual art in Poland, was also conceived with similar intentions. Just as today “Didactic Exhibition on Abstract Art” does not interest us as some excellent product of exhibition design, proto-conceptual art work (exhibition without original works, exhibition of copies, translations and quotations) or a curatorial concept which defines one view of a particular period of art, but rather as a material trace of a culture, of a society and its cultural policies in which in one period it was not only realistically possible to create but even to conceive of such a cultural event, thus the presentation of the symposium in Wroclaw also proposes the examination of the myth which interprets that event exclusively from the perspective of artistic dissent against official cultural policies, or as a “last gathering of the avant-garde”, or as the “first event of conceptual art in Poland”.

The exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” considers the “politics of exhibiting” and, by including historic works and new productions, archive material and research documentation, reconstructing and reinterpreting paradigmatic artistic and exhibition positions from the 1950s until today, shows the historical continuity of similar art experiments which question the social role of art. The focus of this interest is what Peter Watkins expresses in Deimantas Narkevičius’ film The Role of Lifetime (2003) – which consists of an interview with Watkins, a pioneer of so-called docudrama and presents a kind of manifesto of both artists – when he said: “I don’t believe or I’m not interested in the idea of a neutral artist, even if there were such a thing, I don’t think it interesting very much, frankly.” The exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” extracts the presented works from the neutrality imposed by the prevailing consensus, which sees the involvement of art in emancipatory social processes as ideological and social ballast.

Although it presents many historical works, the exhibition has no pretensions to be “museum-like” either on the level of conceptual coherence or by a museum staging. The exhibition has emerged as a result of a two-year collaborative project of the organisations tranzit. hu from Budapest, Muzeum Sztuki from Lodz, Centre for New Media kuda.org from Novi Sad and What, How and for Whom/WHW from Zagreb. Through various formats the project deals with topics connected with the modernistic inheritance and joint history, across the recontextualisation of different art practices, of which many are not directed towards the production of art objects and their aesthetic evaluation but towards mediation and communication of an artwork with a wider public than the usual gallery-goers. The research was directed towards a specific historical, economic and political context and also towards the forming of internationally recognised “universal” norms, in relationship to which the exhibited art practices try to affirm historical continuity and to question their own context. As the result of years of collaborative practice, the exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” is based on the temporary and current constellation of ongoing research trying to draw parallels and define touching points of different related practices, and despite the accent on art production from Eastern Europe, in no sense is there any ambition to offer a homogenising picture of the “Eastern European” art of the last few decades, nor to yield to statistics as a policy of presentation. The proposal of the exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” is not to draw conclusions from the fact that many art positions which would justifiably deserve to be exhibited are missing, nor from the politically incorrect generational, geographical and especially scandalous gender imbalance (two female artists as opposed to eighteen men and eight group projects), but from the interpretation of relationships which show in what way art entered into tensions and conflicts with the cultural hegemony of the moment, in its relationship to both the institution of Art and art institutions. The exhibition examines the question of autonomy of art and political involvement outside the simplifying and prevailing understanding in which political involvement negates autonomy of art, and the art production of Eastern Europe is reduced either to a (delayed) reaction to events in the West or to an instrumentalised ideological construction.

The traditional geopolitical concepts of East and West today seem too simplistic to describe the complex movement of capital and its territorial repositioning in the last few decades. But that does not mean that there has been a change in the prevailing thought or rhetoric about the centre and a periphery which constantly trails after it, through which post-communist countries are defined as cultural spaces in which modernism has been halted for decades, and which now it is necessary to integrate into the global capitalistic system through the process of “transition”. Nor it means that the previous divisions, economic disparities and inequalities have simply vanished. It is a paradoxical fact that in the dominant discourse of the art history, Eastern Europe indeed did not exist during the time of the Cold War division into blocks, except as a cliché used for the purpose of ideological instrumentalisation of the autonomy of art. In fact it only exists as a concept in the art world today, when the processes of its historicisation and building of its narrative have to a certain extent been established, and what still needs to be done is to deconstruct the hegemonic narrative of the West and point out the ways in which it continues to determine the economic relations of art production. The case of socialist Yugoslavia indicates those changes effectively, because after 1948, thanks to its independent and later non-aligned politics, Yugoslavia was mainly not thought of as part of Eastern Europe – to which the Eastern Bloc countries under direct Soviet influence belonged. Only after the fall of the Wall and breakup of Yugoslavia at the beginning of the 1990s, did Yugoslavia and the countries which emerged from it become more and more part of that new “former Eastern Europe”. That does not mean that Yugoslavia was not in many ways “objectively” part of Eastern Europe, but that the very concept of “(former) Eastern Europe” is a changeable ideological construct.

“Art Always Has Its Consequences” starts from the art of the “former” Eastern Europe bearing in mind the question of Romanian philosopher Ovidiu Tichindeleanu: “For what point is there a discussion about East European debates on communism if not to look there for a renewal of the left theoretical tradition?” (5) The exhibition approaches the question of the relationship to the collective amnesia of the progressive achievements of the past, attempting to offer an aesthetic and political jigsaw which can help us reformulate questions connected to today’s moment of acute crisis of the political imagination which came about as a consequence of the tectonic shifts after 1989, and also to the place and role of art today – which questions it can open, which it does not succeed in addressing, and how does art deal with its (in)capabilities? What can we learn from the continuity of the endeavours and art experimentation that characterise art's engagement in the public space? How do gestures of political agitation and protest react to the contracting and closing of public space and the crisis of the concept of the public in different situations, from “real socialism” in Hungary in the 1970s, as in the works of Tibor Hajas and Gyula Pauer, to neo-liberal Romania after its successful accession to the European Union in the recent work Auto-da-Fé by Ciprian Mureşan? Can we see the performance Lenin in Budapest of Bálint Szombathy from 1970, in which the artist wore a poster with a picture of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, as a part of the same continuity, or is it more productive to read his relationship to official political propaganda in the light of what later occurred in the context of Neue Slowenische Kunst? What connection between political involvement, the international history of the left and art production is made by the activist ambient sound installations of the collective Ultra-red founded in the late 1990s in Los Angeles? How to conceive the dynamics of the relationship of subversion and agitation in the controversial poster for the 1987 Day of Youth by the Slovenian New Collectivism, in the political illustrations of Milan Trenc in the high-circulation magazine Start in the late 1980s, or ten years later in the anti-fascist/feminist intervention of Sanja Iveković in the magazine Arkzin, which in the second half of the 1990s developed from a fanzine of the anti-war campaign into a low-circulation and unprofitable, but intellectually extremely important critical and theoretical magazine?

The contextualisation of the contradictory processes through which various ideological processes and social development broke up in the wider context of cultural work, including the fields of design, visual identities, public media and popular education, is addressed by the inclusion of the project “As soon as I open my eyes, I see a film (cinema clubs and the Genre Film Festival/GEFF)” by curator Ana Janevski, which examines the experimental film production of amateur cinema clubs in Zagreb, Belgrade and Split and the connections with the art events of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the project “The Ideology of Design: Fragments about the History of Yugoslav Design”, in the curatorial interpretation of the collective kuda.org from Novi Sad, which studies the development and perception of design in relation to art practices and critical discourses.

How does the interweaving of art and social action reflect on the polemics over the “autonomy” of art, how is a certain practice recognised, legitimised and defended as art in a given moment? How was autonomy understood by Dimitrije Bašičević, a member of Gorgona, prominent critic and curator who has for decades created works almost in secrecy under the pseudonym Mangelos, and whose art mostly started to enter the public space only after the retrospective exhibition of Gorgona in 1977? Did the need for autonomy dictate the action of the enfant terrible of Polish post-avant-garde, artist, poet and musician Andrzej Partum who from the 1960s acted outside the existing structures, revealing the absurdities of social and art life?

What is today the legitimate pedagogical and didactic function of art, which from the historic avant-garde has propelled art movements for decades, such as the movement of Mexican muralists, whose exhibition held in a Ukrainian village in the 1960s is starting point for the video by Sean Snyder? And how and with what aim was this pedagogical and didactic function used in the films of the Béla Balász studio from the 1970s, or in the contemporary works of Andreja Kulunčić? Is there continuity between the relationship towards art institutions and ambitions of exiting the institutions that were the basis of the direct actions of the 1970s, and the art endeavours of today? Should we look for an answer within the wide field of art practice which since the 1990s has been called institutional critique, or, as in case of Yugoslavia, is the idea which formed the critical relationship towards the system of institutions in the work of many groups and artists of the 1970s based on critique of the bureaucratisation and ossification of socialism – as in the work of Vlado Martek and Mladen Stilinović, members of the Group of Six Authors – today inconceivable? Can the institutional and critical interventions of Tomo Savić-Gecan be explained exclusively from the perspective of the global art world that was formed in the 1990s, and without looking at the past? How to understand the fact that the exhibition of Goran Đorđević “Harbringers of the Apocalypse”, held in 1981 in Gallery SC in Belgrade, the Gallery of Extended Media in Zagreb and Gallery ŠKUC in Ljubljana, had such an important influence on the Ljubljana scene of the 1980s.

***

The exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” presents works and exhibition projects which encourage the formulation of questions and their implications, presenting the works in a key which interprets them as critique and rearticulation of the political, cultural and art constellations, as direct action or agitation, or as a symptom which tells us what is possible and acceptable in a given socio-political context. The fact is that the film Centaur (Kentaur, 1973–75) by Tamás St. Auby, a lucid and sharp criticism of the alienation and degradation of the work in a society which appealed to the values of communism, was immediately banned, with the author spending years in exile, but it is also the fact that it was possible to shoot such a film in the 1970s in the oppressive circumstances of Hungary’s cultural policies, in the state-financed Béla Balázs studio which enabled the production of avant-garde experimental films.

The title “Art Always Has Its Consequences” is taken from the conceptual text of Mladen Stilinović “Footwriting” from 1984, and refers to research of the relationship which art has with reality, but also to the equal importance of internal, intrinsically art procedures by which art is repeatedly “limited” to the field of art. Questions of the responsibility of art to its own procedures and the extension of its own boundaries, in connection with self-positioning of an artist both in the system of art and in the wider socio-political context, have not been resolved by the contemporary transformation of the cultural field into a colony of marketing and profit, nor by the fact that the important function which neo-liberalism has given to contemporary art has stimulated its drowning in the creative industries. Indeed, these questions seem more important today than ever.

The exhibition “Art Always Has Its Consequences” places in dialogue historical and contemporary art positions and considers the relationship of collective identities and cultural homogenisation, and the role that art institutions have in these processes. The exhibition is being held at the Kulmer Palace on Katarina's Square in Zagreb, and the presented art works and investigations are confronted with the material and ideological memory of the building itself, which for years served as the main space of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, later renamed to the Museum of Contemporary Art. The building was nationalised after the Second World War and then denationalised again a few years ago, and its character is inseparable from the institutional context that it had for decades, right up to the relatively recent move to the newly-built building of the Museum of Contemporary Art in New Zagreb. This baroque palace and the former space of the museum has been left in the state in which it was found, and besides the former exhibition spaces, the "Art Always Has Its Consequences" also takes part in museum’s former offices and depot, previously invisible to the visitors.

This choice of location does not mean aligning with the current political cultural conjunction which attempts to acquire cultural capital by a general criticism of the museum as an element of cultural tourism, and of the conjuncture between the culture and economy in the city with all consequential embezzlements and contaminations. Neither does it mean to lean towards the euphoric valorisation of the recently opened Museum of Contemporary Art. This temporal occupation of the location of the museum’s former building appeals to the institution’s historic memory and its role in the processes of forming and maintaining collective memories and articulation of collective interests which are not completely overshadowed by topics imposed by the realpolitik, and mainly electoral, rhythm of fictional democracy. The exhibition confronts contemporary approaches with the strategies used in the past, inviting the reading of the presented works in relation to the questions of the role and responsibility of public art institutions, the way in which they are positioned towards the economic and ideological circumstances and the way in which they contribute to the forming of cultural influences and hegemonisation of certain norms.

The exhibition “Art always has consequences” opens on 8 May, on the Day of the Liberation of Zagreb in 1945. Today, at a time of epoch-making realignment in relation to the Second World War and the tendency of equating Nazism and Communism under the general term “totalitarianism”, this choice of date is dedicated to the emancipatory sequence of the National Liberation Struggle as the basic point of reference from which we can look into the future.

(1) GAAG was founded on 15 October 1969 in New York by Jean Toche, Jon Hendricks and Poppy Johnson. Virginia Toche and Joanne Stamerra were included in many aspects of GAAG’s work. Toche and Hendricks still continue to work today on occasion, but the main period of the group’s activities was from 1969 to 1976. The majority of their actions were executed between 1969 and 1971.

(2) A coalition of artists, writers, critics and museum staff founded in New York in 1969 with the aim of putting pressure on museum institutions to reform themselves towards greater democracy.

(3) Ivan Picelj, Radoslav Putar, Tihana Ravelić, Vjenceslav Richter, Neven Šegvić, Vesna Barbić and Edo Kovačević

(4) Hall of the Army in Siask (December 1957), Museum of Applied Arts in Belgrade (January 1958), Advisory Body for Education and Culture in Skopje (March 1958), Tribune of Youth in Novi Sad (May 1958), City Museum in Bečej (June 1958), City Museum in Karlovac (April 1959), Art Gallery in Maribor (June 1959), Museum of Srem in Sremska Mitrovica (February 1960), Artstic Gallery in Osijek (April 1960), Youth Club in Zagreb (December 1961), City Museum in Bjelovar (February/March 1962)

(5) Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, “Towards a critical theory of postcommunism? Beyond anticommunism in Romania”, Radical Philosophy, no. 159, 2010.